Restored view of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE.

Restored view of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE.

The ziggurats erected in Mesopotamia were seen as symbols of the city-state and proved the wealth and social stability of the city-states. They were erected in the center of the city and were the bases for the temples to the state’s chief god. The gods of Mesopotamia seem to be the first deities of the sky, not of the earth; the rulers and priests of the state were the gods’ representatives on earth. The White Temple is probably dedicated to Anu, the sky god, and was only built to accommodate a select few, namely priests and priestesses and leading community members, this is reflected in the bent-axis plan at the top of the stairs. The temples were referred to as “waiting rooms” and would be where the priests and priestesses would literally wait for the deity to descend from the heavens.

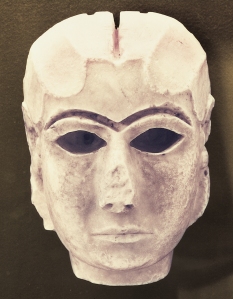

Female head (Inanna?), from Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE. Marble, 8″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

Female head (Inanna?), from Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE. Marble, 8″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

The white marble used for this female head would have been imported at great cost as fine stones for carving were scarce and used sparingly. It’s possible the statue is an image of Inanna since it was found in the sacred precinct of the goddess, but the actual subject is unknown. The head is actually just a face with a flat back; it may have been attached to a wooden body. The appearance originally would have been much more vibrant, the eyes and eyebrows would have been filled with colored shell or stone. A wig, probably made of gold leaf, would have been anchored to the top of the head in the deep groove. The wooden body would have been covered with expensive fabrics and jewels.

Presentation of offerings to Inanna (Warka Vase), from Uruk(modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE. Alabaster, 3′ 1/4″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

Presentation of offerings to Inanna (Warka Vase), from Uruk(modern Warka), Iraq, ca. 3200-3000 BCE. Alabaster, 3′ 1/4″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

The Warka Vase is the first great work of narrative relief sculpture known. It was found in the Inanna temple complex and depicts a religious festival in honor of the goddess. The vase is divided into registers with all of the figures standing on a common ground line (this form would remain the norm for narrative art in Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, and Greece for a millenia). The lowest band shows wheat and other crops above a water line. The next register has ewes and rams moving left to right (the produce and alternating male and female animals are signs of fertility). The third register depicts a procession of naked men moving right to left and carrying baskets and jars overfilled with the earth’s abundance. The men are presented in a composite of frontal and profile views, this approach to representation is called conceptual representation. The uppermost band is a female figure with a tall horned headdress next to two large poles that are the sign of Inanna. Inanna is being presented with offerings by a nude male figure and to the right of her is a partially clothed man who is usually considered a priest-king. The size of Inanna and the priest-king indicates their importance.

Statuettes of two worshipers, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum, shell, and black limestone, man 2′ 4 1/4″ high, woman 1′ 11 1/4″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

Statuettes of two worshipers, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum, shell, and black limestone, man 2′ 4 1/4″ high, woman 1′ 11 1/4″ high. National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad.

Sculptures such as these were reverently buried beneath the floor of a temple at Eshnunna. These are the two largest figures, all made of soft gypsum and inlaid with shell and black limestone, and the collection ranges in size from well under a foot to about 30 inches tall. The statuettes represent mortals in a gesture of prayer with their heads tilted upward for their deity to appear (“waiting room”). Their hands would have held small beakers used for libations. The purpose of these votive figures was to offer constant prayers to the deities in the sky so their oversized eyes symbolize the eternal wakefulness necessary to fulfill their duty.

Peace side of the Standard of Ur, from tomb 779, Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, shell, and red limstone, 8″ X 1’7″. British Museum, London.

Peace side of the Standard of Ur, from tomb 779, Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, shell, and red limstone, 8″ X 1’7″. British Museum, London.

War side of the Standard of Ur, from tomb 779, Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone, 8″ X 1’7″. British Museum, London.

War side of the Standard of Ur, from tomb 779, Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone, 8″ X 1’7″. British Museum, London.

Found in tomb 779 of the Royal Cemetery at Ur where the leading families of Ur were buried, the Standard of Ur is probably the most significant object found in terms of the history of art. The wooden box was inlaid with lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone and is seperated into two sides which are usually referred to as the “peace side” and the “war side”. Each side is divided into three registers and read from left to right and bottom to top. The “peace side” has the lowest band featuring men carrying provisions on their back; above them is a procession of attendants transporting a variety of animals and fish, both registers’ occupants seems to be offering supplies to the banquet depicted in the uppermost register. The banquet features the hierarchy scale that is popular in Mesopotamian art and art found throughout history. The “war side” features a bottom register with four ass-drawn, four-wheeled war chariots crushing enemies, who lay on the ground in front of and beneath the animals. The artist suggests the acceleration of the asses by changingguitar gait. The second register has foot soldiers gathering up and leading awacaptured enemies. The top register shows the naked and degraded foes being brought to the king, who again has been made larger to show hierarchy. The purpose of the Standard of Ur isn’t entirely clear, the suggestion that it would be presented on a pole as a kind of military standard is the reason for its name. With no inscription explaining what it was used for or if the sides present a narrative together, historians can only speculate but still appreciate it for its value as a major piece of art.

Bull-headed harp with inlaid sound box, from the tomb of Pu-abi (tomb 800), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, gold, lapis lazuli, red limestone, and shell, 3′ 8 1/8″ high. British Museum, London.

Bull-headed harp with inlaid sound box, from the tomb of Pu-abi (tomb 800), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, gold, lapis lazuli, red limestone, and shell, 3′ 8 1/8″ high. British Museum, London.

A bull-headed harp like this one is seen being played on the “peace side” of the Standard of Ur so when it was found in the tomb of Pu-abi it was able to be reconstructed. The bull’s head is a wooden core fashioned with gold leaf and caps the harp’s sound box. The bull’s hair and beard are made of lapis lazuli, as is the inlaid background of the soundbox.

Sound box of the bull-headed harp from tomb 789 (“King’s Grave”), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq,ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, and shell, 1′ 7″ high. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Sound box of the bull-headed harp from tomb 789 (“King’s Grave”), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq,ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, and shell, 1′ 7″ high. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

The figures featured on the sound box of the harp are shell and red limestone and are seperated by registers. The bottom register features a scorpion-man in composite and a gazelle bearing goblets. Above them are an ass playing the harp, ajackal playing the zither and a bear steadying the harp or dancing. The second register from the top has a dog wearing a dagger and carrying a laden table with a lion bringing the beverage service. The uppermost register features the hero, also in composite, embracing two man-bulls in a heraldic composition. The meaning behind the sound box depictions is unclear but could be of funerary significance, suggesting that the creatures inhabit the land of the dead and the feast is what awaits in the afterlife. In any case, the sound box provides a very early specimen of the depiction of animals acting as people that will be found throughout history in art and literature.

Banquet scene, cylinder seal (left) and its modern impression (right), from the tomb of Pu-abi (tomb 800), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Maqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Lapis lazuli, 1 7/8″ high, 1″ diameter. British Museum, London.

Banquet scene, cylinder seal (left) and its modern impression (right), from the tomb of Pu-abi (tomb 800), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Maqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Lapis lazuli, 1 7/8″ high, 1″ diameter. British Museum, London.

Excavators of Pu-abi’s tomb found three cylinder seals, one of which gives her name in cuneiform script. A cylinder seal consists of a cylindrical piece of stone engraved to produce a raised impression when rolled over clay. They could carried around and signified high positions in society, used to identify documents and protect storage jars and doors against unauthorized opening. This cylinder seal is divided into two registers; the bottom register with two male attendants serving two seated men and the top with a woman (Pu-abi) sitting and drinking with a man, attended by servants. The hierarchical scale is employed as well as the composite form.